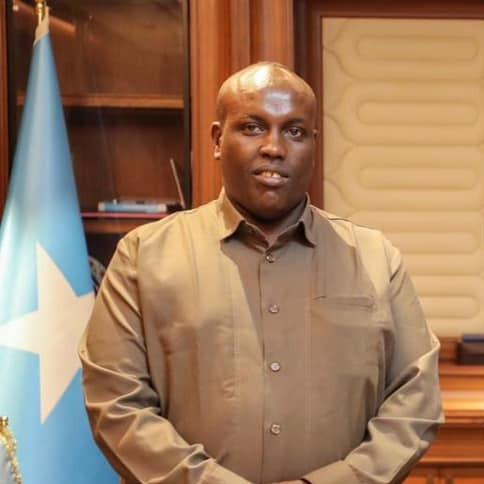

As the Gambia goes to the polls on December 4, 2021, the MFWA’s Senior Programme Officer for Freedom of Expression, Muheeb Saeed, throws light on the remarkable progress that the country has made in the freedom of expression space over the past five post-Yahyah Jammeh years.

For his personal involvement in, and endorsement of numerous outrages perpetrated against journalists, activists and outspoken opponents of his brutal regime, Yahya Jammeh was crowned West Africa’s King of Impunity by the MFWA in 2014.

Among Jammeh’s star victims was Deyda Hydara, editor of The Point newspaper and outspoken critic, who was shot and killed on December 16, 2004. Another emblematic victim was Chief Manneh, a journalist with the Daily Observer newspaper. Manneh was arrested and detained by then National Intelligence Agency (NIA) and eventually disappeared. Musa Saidykhan, editor-in-chief of the Independent newspaper, now defunct, was arrested and severely tortured in detention. The three became the dismal trademarks of Jammeh’s brutal crackdown on the media. Threats could not be taken lightly, and so several journalists fled the country after receiving death threats.

President Yahya Jammeh kept the justice system under his thumb and manipulated a largely partisan legislature to enact a raft of repressive legislation aimed at stifling dissent. In 2013, for instance, the National Assembly amended the Criminal Code to increase the penalty for “giving false information to public servants” (Section 114). The Prison term for breaches was increased from six months to up to five years.

In July 2001 the Gambian Parliament passed the highly-controversial and liberticidal National Media Commission Act. Among other ludicrous provisions, the Act imposed annual licensing on journalists, with the Commission clothed with discretionary powers to renew or refuse applications from journalists and media houses. The Commission was also granted the power to force journalists to reveal their sources. Curiously, all these new regulations were not to apply to the government-owned or controlled media. Driving the final nail into the press freedom coffin was a provision insulating all decisions of the Commission from being contested in court.

In a country where the average salary currently stands at Dalasi 16,000 (about US$310), Parliament in July 2013, passed the Information and Communication (Amendment) Act which imposed a fine of US$74,690 for spreading false news. The law was perceived to be aimed at stifling dissenting opinions and especially targeted at journalists, bloggers, human rights activists and critical citizens.

New Dawn

In December 2016, Jammeh was voted out and forced into exile, ending 22 years of one of Africa’s most brutal dictatorships. Four years after his exit, a new era is emerging. From the notoriety of being among the countries with the worst freedom of expression (FOE) environment in West Africa, The Gambia is gradually shedding that unenviable image, and fast establishing itself among the superstars of the sub-region.

Since the news administration took over, The Gambia has been making impressive strides on the political and freedom of expression (FOE) fronts that have seen it competing favourably with Ghana and Senegal, two of the region’s shining lights in democracy and press freedom. The Afrobarometer Report 2021 affirms that “An overwhelming majority of Gambians say the media is in fact free to do its work without government interference.”

The Media Foundation for West Africa’s (MFWA) monitoring recorded a total of five violations in 2017, a significant improvement over the 13 violations bequeathed by the Jammeh regime in its final year. With only four violations, 2019 was the least repressive of the past four years under President Adama Barrow’s stewardship.

The country in 2018 recorded eight violations, the country’s worst record since Jammeh’s departure. The total number of violations recorded in The Gambia over the past four years, therefore comes to 25, same as Senegal’s for that period, and much better than that of Ghana which stands at 79 violations over the same space of time. Additionally, violations recorded in The Gambia in the three worst years of the Barrow regime – 2017 (five) 2018 (eight) and 2020 (eight) – stand at 21, same as Ghana’s total for 2020 alone.

The Gambia ended the first quarter of 2020 (January-March) with 7 violations and recorded a single violation in the second quarter (April-June, 2020), eventually rounding up the year with eight violations, having remarkably gone incident-free during the entire second half of the year.

What is even more significant, the single violation recorded on June 21, 2020, stood for ten months – that is until April 19, 2021. In that incident, the police detained Ebou N. Keita, an editor and camera operator with the privately-owned Gambian Talents Television. The journalist was covering a protest against COVID-19 restrictions when the security officers arrested him for filming their operations.

On April 19, 2021, a group of prison wardens manhandled Yankuba Jallow of the Foroyaa newspaper at a court premises in Banjul after he refused an order to surrender his phone. He had been accosted for filming a group of remand prisoners after court proceedings. The ten months’ interval is the longest respite and a remarkable milestone in a country where press freedom violations was a daily nightmare for journalists during the Jammeh era.

President Adama Barrow’s four-year-old regime is putting The Gambia through effective press freedom rehabilitation with encouraging results so far. It is carrying out reforms to the legal frameworks to guarantee freedom of expression and access to information. The attitude of government officials and security agents towards the media and public criticism has greatly improved. For example, following the last incident mentioned above, the director of prisons met the aggrieved journalist and rendered an apology. Under Jammeh’s rule, the journalist would not have dared defy a security officer’s orders, albeit unlawful, to surrender his phone. Such resistance would have been judged foolhardy and would most probably have attracted a few hefty slaps, kicks and/or detention.

The notorious National Intelligence Agency (NIA), Yahya Jammeh’s pet instrument of repression, has been renamed State Intelligence Service and stripped of its extensive powers of coercion. Additionally, several former NIA officials have been arrested and are facing trial for their roles in human rights abuses, including press freedom violations, and media houses arbitrarily shut down by the previous government have been reopened.

In June 2018, the Adama Barrow-led government paid some compensations to the families of the Ebrimah Manneh and Deyda Hydara, who, together with Musa Saidykhan, became the symbols of former President Yahya Jammeh’s brutal crackdown on critical journalists. The deal was struck through the mediation of the MFWA and its national partner organisation, the Gambia Press Union (GPU), with support from IFEX.

The facilitation role played by the MFWA and GPU was part of engagements with the Gambian government to support and strengthen the Gambian media sector to contribute effectively to the democratic transition processes in the country after the fall of Jammeh.

The MFWA and its partner organisation, the Gambia Press Union, are proud to have contributed to the remarkable improvement in press freedom in The Gambia.

Media Law Reforms

On July 1, 2021, Gambia’s National Assembly approved the Access to Information Bill 2021 in a major milestone in the country’s march towards genuine democracy in the post-Yahyah Jammeh era. President Adama Barrow subsequently signed the bill into law in August to give Gambians, for the first time in the country’s history, the legal right to demand public information. The adoption of the law crowned five years of advocacy and stakeholder engagements and was hailed as a major boost for fact-based and investigative journalism.

On May 9, 2018, the Gambian Supreme Court’s declared as unconstitutional the country’s law on criminal defamation. The ruling followed an April 2017 civil suit filed by the MFWA’s national partner organisation, Gambia Press Union (GPU). With regard to sedition, the Court said that sedition could be established if the alleged defamatory material targets the person of the complainant. However, it said there is no sedition when the target is the government as an institution.

The improved press freedom environment has encouraged the proliferation of private broadcasters and online media outlets with media pluralism on full display.

Lingering Concerns

Despite the massive improvement, some concerns still linger. For instance, a constitutional reforms process has come to unstack with parliament failing to endorse the new draft constitution. The government had initiated the process in line with its electoral promise to rebuild the foundations for good governance and democracy in The Gambia.

Among the proposed innovations was a presidential term limit with retrospective effect for the incumbent, curbs on the powers of the Executive, a minimum of a bachelor’s degree for presidential candidates and political inclusion of marginalised groups (including women, youth and people with disabilities). It is a huge disappointment and a waste of two years of efforts that included broad consultations and enjoyed massive support.

A few attempts by the government to test the pulse of the media have ruffled more than a few feathers. In March 2019, the authorities introduced a new security screening for journalists seeking accreditation to cover the Presidency. The procedure, which involved appearing before the State Intelligence Service for scrutiny, was denounced as too intensive and liable to discriminatory use to favour or target certain journalists and media houses. After a strong backlash, the policy was withdrawn.

While this incident was interpreted as evidence that government would not spare the opportunity to suppress the media, others pointed to its withdrawal as a sign that the new Administration is responsive to the media’s concerns.

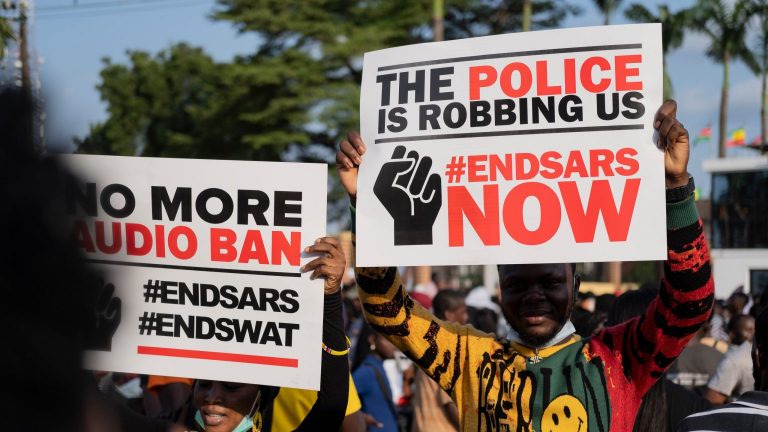

On January 26, 2020, there was a massive crackdown on demonstrators who were demanding the coalition government’s departure in line with its promise during the 2016 election campaign to stay in power for only three years. The constitution provides for a five-year term, but the demonstrators were holding the government to its campaign promise, after three years in power. Security forces arrested dozens of demonstrators, shut down three radio stations and arrested four journalists, including editors, throwing the country into a shock and reviving chilling memories of the Jammeh era.

The Gambia has a small and weak economy which translates into a tiny advertising market. This poses a major sustainability problem for the media which has been hard hit already by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are also lingering concerns about the media laws. The Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling which decriminalised the spreading of false news online, left intact sections of the criminal code that penalise similar offences with fines and even prison terms.

The President of the GPU, Sheriff Bojang, fears the government can press the buttons of this repressive legal machinery whenever it likes.

“While we celebrate the gains in The Gambia as far Press freedom is concerned, we are disturbed and worried that some of the repressive media laws used by the Yahya Jammeh regime to imprison and harm journalists are still existing under President Barrow. As we get closer to the December presidential election, we are concerned that journalists might be targeted by the security forces as well as political party militants,” Bojang told the MFWA in a telephone interview back in July 2021.

The elections are just a week away and, fortunately, the campaigns have proceeded smoothly with the media allowed all the space to do its work. There have so far been no incidents of attacks on journalists and no major professional breaches by the media. The MFWA urges the media to maintain its professional posture in reporting issues and moderating the political debate to educate and inform the electorate.

Despite the gains made in the press freedom space, there is still some work to be done to put The Gambia on a strong democratic footing. We, therefore, urge the government that will emerge from the December 5, 2021 elections to carry on with the review of the media legal framework to eliminate all repressive elements. In particular, the new government must expunge the remnants of the Criminal Code that restrict press freedom and freedom of expression in The Gambia. We wish the people of The Gambia successful polls and a peaceful outcome.